As a dog trainer, a significant part of my career focuses on methodology. At some point I had to make some decisions on what sorts of dog training methods I would be using to teach clients, what methods I wanted to learn more about, and which methods I would avoid. I’m not one for going with the flow, or doing something because someone told me to (there’s a reason I’m my own boss now!). I spent a lot of time thinking about what made the most sense to me; I want to be effective, and create procedures that clients can easily follow. The most important thing to me is that the methods I use work across the board, with minimal adaptation, for all dogs. This is important to me because my goal isn’t to teach an owner how to train one specific task with one specific dog. I want to impart enough information that someone could apply this to their next dog without having to think about whether this method is appropriate for this new dog. Is it possible? Absolutely, but it requires us to think beyond what I am calling “the average dog”.

What is the Average Dog?

The definition of average is a mathematical one, reached by dividing the sum of a set of values by their number in the set. So, if we added up all the dog personalities in the world, and divided them by the number of dogs, we have our average dog. Ok, so that doesn’t really make sense, but let’s think about the most middle-of-the-road traits that we see in an average dog population. The average dog isn’t overtly afraid of sights, sounds, or other stimulus. He is friendly with people and dogs, and likes to play, but not obsessively so. He is interested in the world around him, but isn’t overcome with a desire to chase and/or kill prey. He learns new skills easily, but not so quickly as to outthink his human. His energy needs are moderate. He listens to Top 40 Hits.

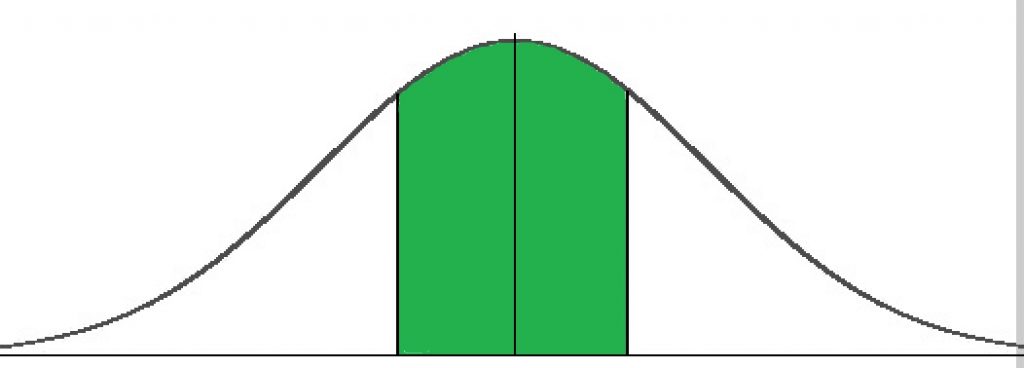

I’ll admit, as a dog trainer, I don’t see many average dogs in my career, and when I do they are generally puppies working on basic manners, or learning one of the sports I teach, Nose Work or swimming. Most of the dogs I see are on one end of the spectrum or the other. When I do come across those average dogs, it helps me to understand how certain punitive dog training methods have persisted, these dogs can take it. I’m not saying that I condone it, but quite honestly, average dogs can handle getting pretty intense corrections without much evident fallout in their overall temperament or affect. These are the dogs that allow traditional, punitive training methods to persist, because they appear totally fine with whatever comes their way, and are socially motivated enough to change behavior based on that information. Here’s the thing – When you set up systems of learning around the average individual, you are going to fail every other individual on either end of the spectrum.

What Happens When we Train to the Average?

The risk of using punitive or aversive methods might be small for the average dog, but it can be quite large for dogs on both ends of the bell curve. The problem is, it’s hard to tell how a dog might respond to a training tool or method before applying it, so you are taking a risk in going down that path to begin with. Some of the common “side-effects” I see from punitive methods include increased aggression, arousal, and/or anxiety, refusal to engage with training, and creating negative associations with innocuous stimuli. Again, just because we don’t see these effects in every dog does not mean that it’s a sound training method. Dogs are incredibly resilient, and just because some dogs can take a correction without having any sign of these negative effects doesn’t mean that it there wasn’t some fallout, and it also doesn’t mean that it won’t have a huge affect on the next dog. What I do know is that using reinforcement based solutions focused on building a relationship of communication and trust between the dog and handler will work well for all dogs, so to me it’s not worth the risk of the potential fallout when we have other options. Using methods that work for dogs on the ends of the spectrum will work faster and more easily for average dogs, so there’s really no argument for using punitive methods on these dogs.

Using an Inclusive Approach

The amazing thing about average individuals, is that almost anything works for them. So why should they be the goal posts? Training should start with a very wide base, and be refined to the individual as you progress. This can be demonstrated by the LIMA model, which I adhere to, which stands for Least Intrusive, Minimally Aversive. I start every client out with the same basic exercises, whether it’s an 8 week old puppy, or a dog with a bite history. These foundations aren’t “obedience” exercises, they focus on three basic skills that I’ve boiled down to; 1) the handler is a home base, 2) don’t rush toward things you want, and 3) relaxing feels good. I believe every single dog needs to understand these concepts before you can move on to really solving any other problem. For the dog to truly understand these concepts they must be broken down into small pieces and reinforced in such a way as to communicate what you want the dog to do. The dog has to have a choice in the matter, because when choice is taken away, the dog is simply performing a series of tasks based on specific cues. This sort of training will break down over time, or you will be stuck micromanaging your dog for the rest of its life. If you teach the dog what behaviors are reinforcing, and give them choices in the learning process, you will create long lasting behaviors.

When choosing a trainer, it is important to find someone whose methods work for all dogs. The problem is, most trainers will tell you their training methods work for all dogs, so how do you know who to trust? My decision in methodology was made through my own experiences in many years working with dogs, because that’s how I tend to do things, but if you are looking for trusted resources there are several. The International Association of Animal Behavior Consultants has the previously linked position statement on LIMA, and the American Veterinary Society of Animal Behavior has several position statements on training, including those on dominance theory and the use of punishment in training. If you are trying to find a trainer to help you solve a behavior problem with your dog, make sure that their methods fall in line with the most current evidence in animal behavior and training research. We know so much more about how animals learn, and how behavior is changed than we did when many of these traditional, punitive training methods were popularized. If your dog falls outside the “normal” range on the bell curve, find a trainer who is skilled in applying these methods with very basic foundations that can build into a significant behavior change.

Redefining our Expectations

It’s okay if your dog isn’t average. Let me repeat that – It’s OKAY if your dog isn’t average. There are so many special and amazing dogs out there that don’t come anywhere close to that middle range we call “normal”. These dogs make great companions for people whose lifestyle fits their needs, and sometimes they are able to teach their humans something about how they might view the world differently. Average isn’t good, it isn’t bad, it just is. Dogs will come into your life that are easy going and perfect in every way, and others will challenge you and cause you to learn new things. That’s what’s great about life with dogs. Good training will enhance your relationship with your dog regardless of where they are on that spectrum, and it won’t come with risks of unintended consequences.